According to studies in discourse analysis, language is important not only as a tool for communicating an idea or reality, but it plays a critical role in producing, constructing and re-shaping ideas and, in turn, reality.

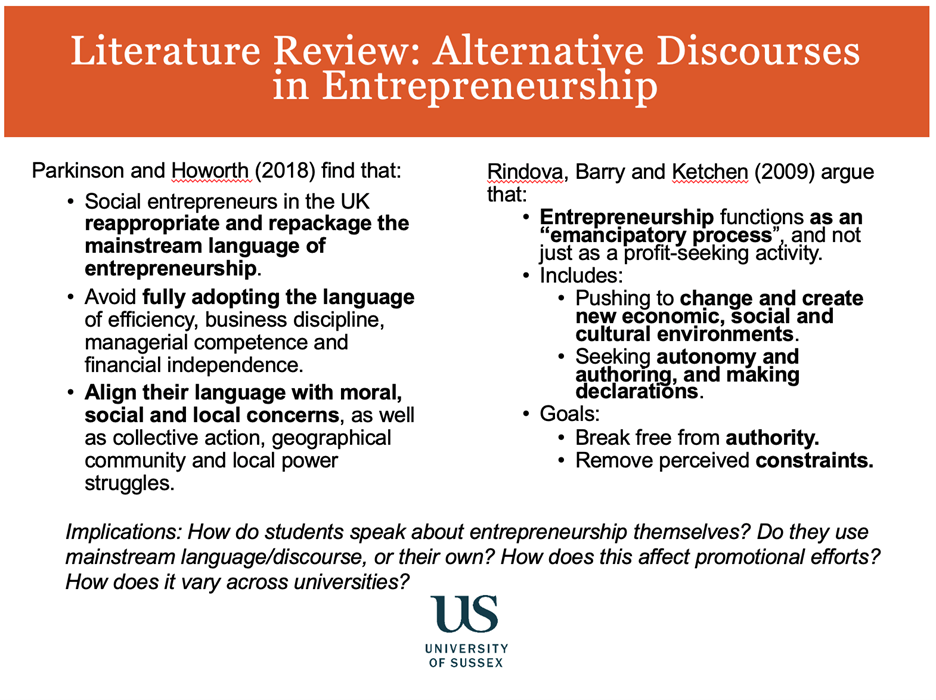

Berglund and Johansson (2007) argue that that the language of entrepreneurship not only communicates entrepreneurship as a practice, but directly constructs and shapes entrepreneurship as a practice. The study finds that there exists a dominant archetype of the “entrepreneur,” associated with assets and qualities including ability to network, high social capital, efficient and managerial. Moreover, wealth creation through profit-maximisation is typically assumed as one (if not the) fundamental goal of entrepreneurial pursuit.

Ostensibly, this discourse may be reflected in what we see in practice in the United Kingdom, where the typical early-stage entrepreneur is male, aged 39, has a university degree, is from a middle to higher income household and is engaged in a consumer-oriented business (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor). In which case, the language used around entrepreneurship may play a part in alienating individuals and groups who do not identify with these qualities or are not motivated by profit maximisation.

For Aspect member institutions, it is imperative to understand the role of language use in reaching and supporting social science student entrepreneurs, particularly underrepresented groups and disciplines in entrepreneurship. Further, playing an instrumental part in the wider entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystem, universities are in a unique position to not only transform the discourse to make the ecosystem more inclusive for underrepresented founders, but also to change the narrative of what it means to be a founder and what kind of activity is considered entrepreneurial.

A changing discourse on entrepreneurship?

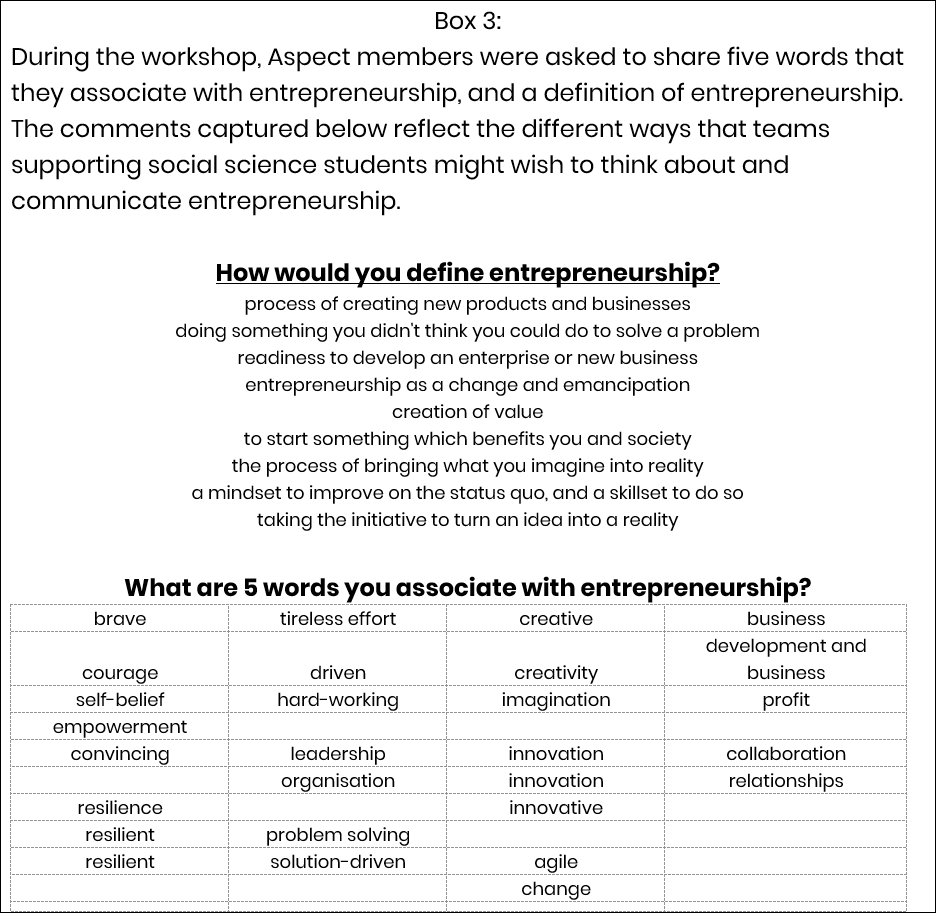

It is within this context that the Aspect Entrepreneurship Community of Practice, hosted by the University of Sussex, led a knowledge sharing Q&A session to discuss and exchange learnings in this area.

Source: Aspect Entrepreneurship Community of Practice. “The Language of Entrepreneurship in Social Sciences” Workshop Presentation, 4 November 2020. Prepared by Emily Bohobo N’Dombaxe Dola at the University of University of Sussex.

Is the discourse changing?

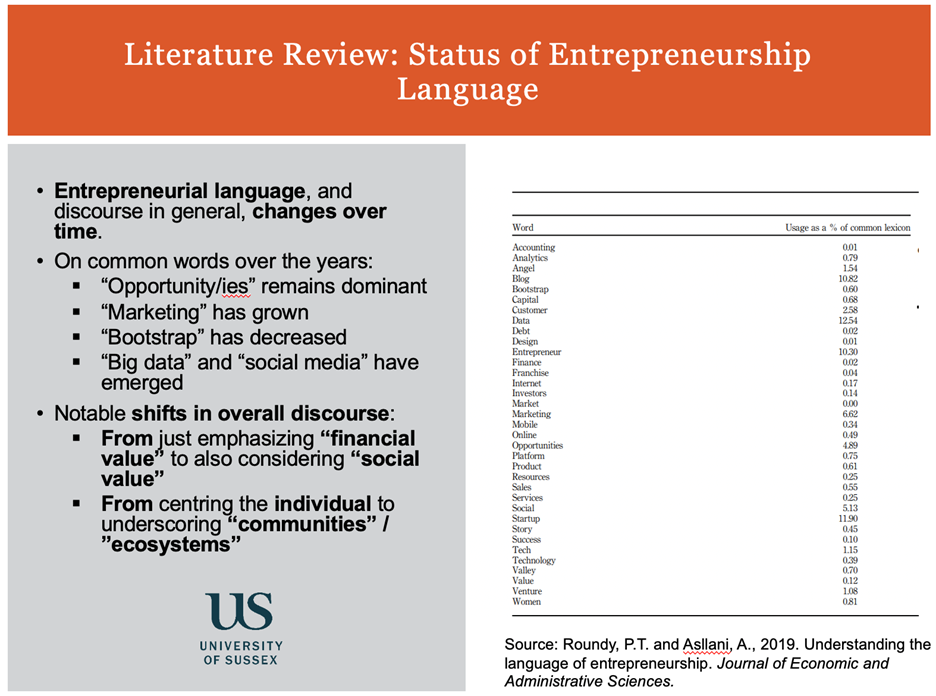

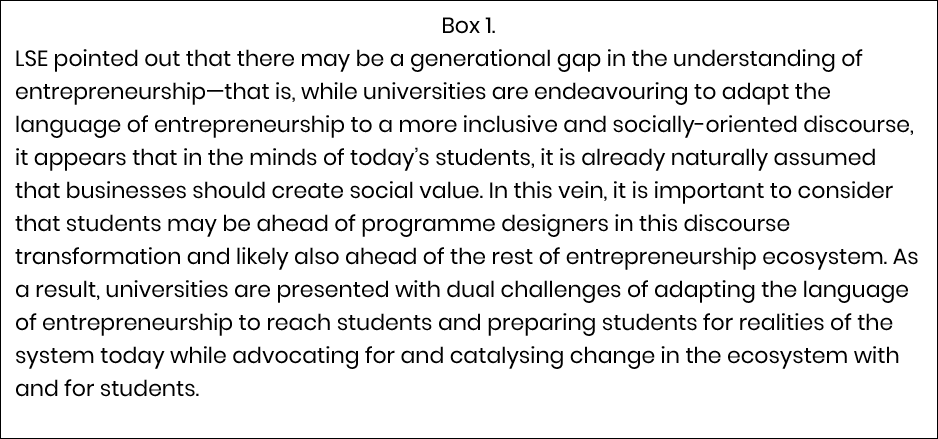

Emily Bohobo N’Dombaxe Dola from the University of Sussex presented on the changing discourse of entrepreneurship. While the modern concept of entrepreneurship has roots in the ‘pro-markets’ era of President Reagan in the United States, recent analysis by Roundy and Asllani (2019) demonstrates notable shifts in the language around entrepreneurship. In particular, there are two notable shifts: (1) from sole emphasis on “financial value” to also considering “social value” and (2) from a focus on individuals to underscoring an effect on “communities” and/or “ecosystems.”

Wordcloud based on YCombinator and Entrepreneur First webpages, Accessed on 23 November 2020.

Though it is evident that social impact accelerators have emerged as a category of their own—the most notable of which in the UK is Bethnal Green Ventures—it is not clear whether the leading discourse of entrepreneurship has fundamentally shifted.[1] If we take a look at the webpages of the leading startup accelerators, YCombinator and Entrepreneur First, we see that the most common terms include “startups,” “founders,” “investors,” “money” and “fund.” This discourse appears more in line with the earlier findings from Berglund and Johansson (2007) than indicative of a shift towards social value or underscoring an effect on communities or ecosystems. This terminology also stands in contrast to that seen on the webpage of Bethnal Green Ventures, which includes words such as “impact,” “good,” “social” and “environmental.”

At the same time, leading accelerators such as YCombinator, TechStars and 500 Startups also top lists of best social impact accelerators, beating many, impact-focused accelerator programmes by impact organisations such as Ashoka and Acumen+. This observation may suggest that while there has emerged an alternative narrative for socially responsible business, the dynamics of the ecosystem have yet to transform. Social impact accelerators, as they exist today, follow the same broad structure of looking for scalable businesses and provide guidance and networks in exchange for a percentage of equity in the business. Whether founding a socially impactful or solely profit-driven business, ambitious founders still strive for the same wider network, funding and other resources.

Is there a difference in the language for entrepreneurship in the social sciences?

Next, we posed the question of whether there is or ought to be a difference in the language of entrepreneurship in the social sciences. For Aspect members, we want to understand how language use affects a university entrepreneurship programme’s ability to reach students from different disciplines and, if so, how language can be adapted to better reach the social sciences disciplines. Relatedly, what is the relationship between language that reaches social science students and the emerging narrative of social impact or socially responsible business?

We examined the language used on the webpages of the flagship funding competitions of two Aspect members, LSE and the University of Sussex. LSE is considered an institution with a singular focus on social sciences disciplines, though the disciplines range from finance and management to public policy and anthropology. The University of Sussex is emblematic of an institution offering disciplines across the board from the sciences to social science to the arts and humanities. A quick comparison of the most common words does not indicate a clear difference between the language of entrepreneurship for that of a social sciences institution versus an institution with a broader focus. The discourse appears broadly in line with that of the mainstream discourse, with common terms such as “funding” and “business,” though the university programmes place more emphasis on “support” and “help.” That being said, the About page of the LSE entrepreneurship hub does emphasise that they support “students and alumni at any stage of building a socially responsible business” and Sussex offers a separate Social Impact Prize.

Source: Aspect Entrepreneurship Community of Practice. “The Language of Entrepreneurship in Social Sciences” Workshop Presentation, 4 November 2020. Prepared by Emily Bohobo N’Dombaxe Dola at the University of University of Sussex.

We turn to two founders from the inaugural Aspect Student Accelerator Programme (ASAP) to understand the language that resonates with them. What may come as a surprise is that both Rifhat Qureshi, founder of Modest Trends, and Ash Ryan, founder of Open Source Policy, do not identify with being ‘social science’ entrepreneurs. Going another step back, they did not initially look to start businesses or becoming entrepreneurs.

Six months ago I wouldn’t have known what “social enterprise” was. But I responded to posters around university with statements like “Do you have an idea that could change the world?”

Source: Ash Ryan, Open Source Policy

Both of their journeys started with seeing a problem in the world that they wanted to solve, wanting to be a “vehicle for change” and “make a difference” in a particular space in society. It appears almost circumstantial that their approach to solving the respective challenges came to be what might be called “businesses.” They share a sense of sectoral and methodological agnosticism, and instead endeavour towards what’s optimal in practice to solving the challenge, in terms of analytical approach and obtaining funding and other resources. For instance, Ash shared that, after having been self-employed in the past, she was quite “turned off from the idea of entrepreneurship”, but was drawn back towards becoming a founder earlier this year while researching funding options for a research pilot. For Rifhat, what interested her was the skills you develop as an entrepreneur, i.e. the specific skills and masterclasses advertised by the university entrepreneurship hub caught her attention.

What approaches are universities taking to better communicate to social sciences entrepreneurs?

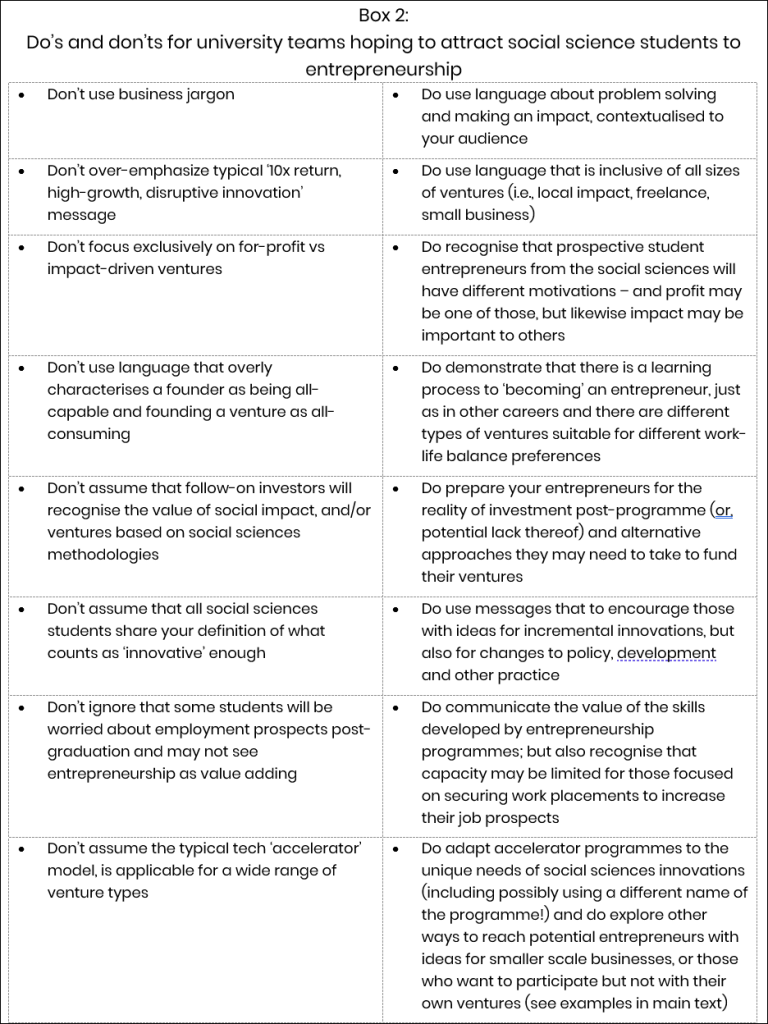

The founders and participants at the workshop also reflected on what support exist for social science entrepreneurs within their institutions, and what might need to be different in terms of how these are communicated to attract social science students, but also whether the programmes themselves need to be different in what support they provide. Feedback is shared in Box 2.

The Aspect members agreed that contextualising entrepreneurship to the values of different audiences works better in terms of engagement, however, this takes resources and must be balanced with the capacity of the team to support a wider range of entrepreneurs. Luke Mitchell from the Careers & Employability Centre at the University of Sussex noted that their institution has taken some early steps towards segmenting their offerings for different ‘types’ of entrepreneurs. For example, they describe entrepreneurship with language like “how can your ideas change the world” which covers the breadth of innovation, social impact and even profit. In parallel, they are developing offerings that go beyond the ‘typical’ start-up venture support, recognising groups like freelancers and side hustlers as viable paths for entrepreneurship.

The Cardiff University Enterprise team are also finding innovative ways to introduce entrepreneurship to students from disciplines like social sciences, that might not normally engage. For example, they run a workshop called ‘Save your Museum’ where participants essentially map out similar questions as they would in a business model canvas exercise (a common tool used to explore start-up ideas). However, the concept is introduced without business jargon and other terms that might cause them to disassociate with the process.

Adapting entrepreneurship support to be more attractive to different disciplines should also take account of the level and scale of impact desired. In Oxford, for example, it was noted that there are programmes that support innovators who want to create impact on a national of global scale (the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship), but likewise programmes like the Oxford Hub are equally important for engaging those that want to make a local impact. The workshop participants agreed that often students can feel that tackling really ‘big issues’ is too overwhelming; communicating the value and role of smaller scale impact could encourage them to engage with entrepreneurship.

The Aspect Marketing Toolkit project may provide another mechanism for exploring this topic further. Led by the University of Glasgow, this project will be examining good practice in terms of how we communicate the value of commercialisation and entrepreneurship to social science students, but also, how we communicate the value of social sciences to the wider world, be that businesses, investors, or even other university departments.

Takeaways

This Q&A session offered a chance for Aspect members to share and reflect on the language of entrepreneurship and what it means for the social sciences. The high-level takeaway is that the topic is as important as it is complex.

On the one hand, while there is an emerging narrative around socially impactful and socially responsible business, it is less clear the extent to which the underlying dynamics of the entrepreneurship ecosystem, as a whole, has transformed. On the other hand, it appears just as unclear the extent to which the discourse of impactful and responsible business expands the reach or appeal of entrepreneurship for those from traditionally underrepresented disciplines. The following include a few takeaways to consider when thinking further about the language of entrepreneurship:

- One aspect that appears consistent is the nature and centrality of financial value. Even if the endeavour itself is not profit-seeking, starting and running an independent endeavour of any type requires funding. Seeking and securing funding requires a venture to organise and narrate itself in line with the conventional framework of financial value. Moreover, being a start-up business opens the doors to a vast global pool of funding. As a result, it is also important to consider potential inadvertent effects of a funding ‘ceiling’ that social sciences and social impact venture founders may face if their endeavour is characterised alternatively.

- Entrepreneurs from the social sciences disciplines do not view themselves as ‘social science’entrepreneurs. For universities that wish to attract more students from the social sciences to entrepreneurship, choosing messages about solving problems and supporting research impact may get better results than language that takes a discipline-led focus. To become better aligned with and better serve students from different disciplines, discussion on the language of entrepreneurship may need to go one step back—perhaps the question is not how to characterise entrepreneurship, but to forego characterising the endeavour as entrepreneurship or business at all.

- Entrepreneurship as we understand it today, offers valuable skills that are also transferrable to different pursuits. Even if students do not become “founders”, the skills and resources offered through workshops by university entrepreneurship hubs are of value to students across disciplines. The process is as important as the outcome.

- Talking to student and alumni entrepreneurs is incredibly useful in understanding what language resonates with them. To probe this topic further, it would be useful to engage a wider range of students, across different disciplines, in a focus group discussion and individual interviews or surveys. That way, we can have more confidence in determining whether (a) what these two founders shared holds true for all students, i.e. there is no difference by discipline and (b) what they shared holds true for the social sciences, only. Then, we can think about how to adapt the language accordingly.

Conclusion

The language we use shapes our reality. However, while research indicates evidence of a changing discourse of entrepreneurship, the reality of the dynamics of the entrepreneurship ecosystem may have yet to catch up. Even if businesses today do not have to have to a singular focus on creating financial value, financial value is still critical when it comes to the funding perspective for start-up endeavours, whether profit-seeking or not.

To better serve and reach students from different academic disciplines, universities have to think outside of the box and listen more closely to the language that resonates with students. Students today may be more motivated by the prospect of solving a challenge and making a difference in society—whether locally or globally—than that of wealth generation. That said, starting a business or developing the skills needed to be an entrepreneur may be still be valuable for achieving or working towards solving a societal challenge.

Therefore, universities may need to consider shifting the primary narrative from “business” and “entrepreneurship” to that of “solving challenges,” while providing an equivalent degree of funding and resources—MIT Solve is a prominent example.

Slides from the workshop

Further reading

For more from the studies reviewed in this workshop, see below:

- Berglund, K. and Johansson, A.W., 2007. Constructions of entrepreneurship: a discourse analysis of academic publications. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy.

- Parkinson, C. and Howorth, C., 2008. The language of social entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship and regional development, 20(3), pp.285-309.

- Pawar, P., 2013. Social sciences perspectives on entrepreneurship. Social Sciences, 3(9).

- Roundy, P.T. and Asllani, A., 2019. Understanding the language of entrepreneurship. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences.

- Swedberg, R. ed., 2000. Entrepreneurship: The social science view. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wen Chen, LSE School of Public Policy ’18

Emily Bohobo N’Dombaxe Dola, University of Sussex, School of Global Studies ‘20

[1] Aspect has funded two social sciences accelerator pilot programmes (ARC and ASAP) both of which include a social impact component to the programmes. ARC is targeted at researchers and includes support in its curriculum for those seeking social impact from ventures; ASAP is for students and alumni and includes social impact as part of its selection criteria. Outcomes and insights from both programmes will be included in Aspect’s final Learning Report in 2021.