Why explore intrapreneurship in the social sciences?

This interest stemmed from three observations by members of Aspect’s Entrepreneurship CoP:

- An observation that international students are more likely to be interested university entrepreneurship programming, while domestic students are more likely to be motivated in securing gainful employment post-graduation.

- A hypothesis that social science students may be more inclined towards becoming ‘intrapreneurs’ rather than entrepreneurs.

- An observation that employers value innovative skills and a self-starting mindset, which are skills fostered by entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship programmes.

If these observations are correct, then, on the one hand, how can Aspect members better communicate the value of intrapreneurship to students in order to motivate participation in entrepreneurship programming? On the other hand, how can they effectively communicate the value of social scientists’ entrepreneurial skills to future employers? And finally, what might intrapreneurship-specific programming for social sciences look like?

To explore these questions further, the Aspect Entrepreneurship Community of Practice (CoP) commissioned an exploratory study of intrapreneurship in the social sciences. The following write-up provides a brief overview of: what is intrapreneurship, how popular is the term, why is it important, and a few examples of university intrapreneurship programmes in the UK and US. The study draws from secondary research of publicly available information as well as insights shared at a Q&A session hosted by the CoP in June 2021 (slides from the session can also be downloaded here).

What is intrapreneurship?

There is no single, agreed-upon, definition for intrapreneurship. In simplest terms, an intrapreneur is someone who acts like an entrepreneur within an established business or organisation. In other words, an intrapreneur is an employee that takes on the mindset of an entrepreneur within a company. That being said, intrapreneurship can take place at any level—individual, team, or even company-wide. Intrapreneurial activity may result in a new business or venture within an organisation. Sometimes the new business becomes a new section, or department, or even a spinoff entity. (See Box 1 for a discussion of the origins of modern intrapreneurship.)

Box 1. Origins of modern intrapreneurship

Though origins of the term are unclear, some cite the beginning of modern intrapreneurship in 1974 when Art Fry and Spenser Silver at 3M created the Post-It Note. Notably, 3M had in place a policy of allowing employees to spend 15% of their time working on their own project ideas—this type of policy supports intrapreneurship and innovation. Today, a number of large tech companies are known for encouraging intrapreneurship through similar policies such as Google’s “20% time” that offers the option for employees to spend time to work on side projects of their choice.

The term is thought to be coined in 1978, when Gifford Pinchot III and Elizabeth Pinchot used the word in their paper Intra-Corporate Entrepreneurship, and again in their 1985 book Intrapreneuring, describing intrapreneurs as “dreamers who do.”

Steve Jobs is also credited with popularising the term in the 1980s. In a Newsweek article dated 30 September 1985, Jobs said of intrapreneurship within Apple,

“The Macintosh team was what is commonly known as intrapreneurship… a group of people going, in essence, back to the garage, but in a large company.”

While Jobs co-founded Apple, it was his intrapreneurial initiative leading a group of Apple employees to work separately from the larger organisation that led to the development of the famous Apple Macintosh in the eighties. Jobs later encouraged and cultivated a company-wide intrapreneurial ethos when he took the helm, enabling Apple to become the brand that it is today.

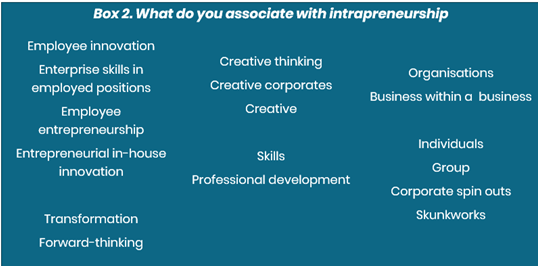

During a Q&A session hosted by the Aspect Entrepreneurship CoP, members were prompted to share words and phrases that they associate with intrapreneurship (see Box 2). The terms shared are largely in line with commonly accepted definitions of intrapreneurship: that is intrapreneurship involves innovation, enterprising or entrepreneurial skills, being creative, can take place at individual, group or organisation-wide levels and can become a new business within a business or a spinout on its own. At the same time, it is also worthwhile to note that any individual understanding of intrapreneurship tends to focus on one or two of the areas, rather than all of these areas.

Source: Aspect Entrepreneurship CoP Workshop Q&A, July 2021

But, just how popular is the term, ‘intrapreneurship’?

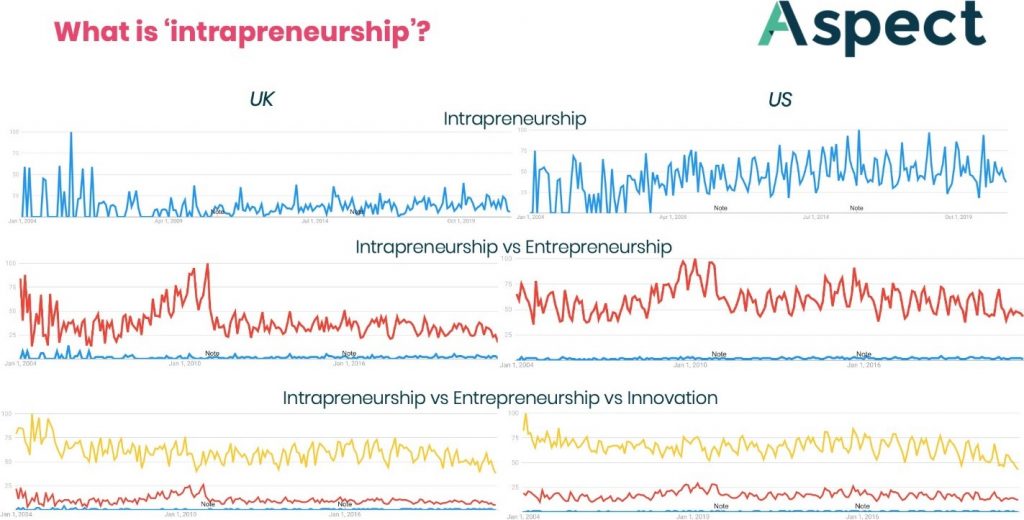

Notably, Microsoft Word’s spelling correction menu does not provide ‘intrapreneurship’ as an option, instead offering up ‘entrepreneurship’ as the closest correct spelling. Google Trends shows that amongst the terms, ‘intrapreneurship’, ‘entrepreneurship’ and ‘innovation’, innovation is the most popular search term; though popularity of ‘innovation’ has also trended down slightly in the past few years (both in the UK and US). ‘Entrepreneurship’ places second in popularity and has been holding relatively steady in the past few years. ‘Intrapreneurship’, on the other hand, is not a common search topic and seems to have dwindled in popularity in the UK since the mid-2000s, though there is a slight uptick in recent years. In contrast, the term is seeing more interest in the US in the past few years. (See Figure 1 for Google Trends charts.)

Figure 1. How popular is ‘intrapreneurship’? Source: Google Trends, accessed June 2021

In line with the Google Trends finding, global recruitment specialist, Michael Page’s 2020 survey showed that when polled, just 15 per cent of workers said they understood the concept of ‘intrapreneurship’ – but when pressed, the majority were unable to accurately explain it. Of those who said they understood, just two in five (37 per cent) provided an accurate definition.

These findings point to the potential issue of a lack of popular usage and understanding of the term, ‘intrapreneurship’. This may pose a challenge for university programmes in designing communication around the value of intrapreneurship and in branding intrapreneurship-specific programming.

Why is intrapreneurship important?

Research by Deloitte states that 88 per cent of the companies on the Fortune 500 list in 1955 did not exist by 2015. Most went bankrupt, a few were acquired, some merged. The two key differentiators for the longest-lived companies were improving their current products and harnessing employee innovation—hence, intrapreneurship is critical to an organisation’s long-run viability.

Intrapreneurship has been named the most desirable skill for 2020 by global recruitment specialist, Michael Page. Once given a definition of the term, nearly two-thirds of workers (62 per cent) say they recognise themselves as intrapreneurial, but just 12 per cent currently list it on their CV, something that the Managing Director of Michael Page UK&I, says job seekers should address to allow themselves to stand out from other candidates.

Intrapreneurship is evidently important to organisations, and employers value intrapreneurial skills. However, going back to the earlier finding that the term ‘intrapreneurship’ lacks popular usage and understanding, there remains a question as to how intrapreneurial capacity and its value can be conveyed most effectively to students and employers.

Box 3. Intrapreneurship is not just for large companies

Though conventional discourse around intrapreneurship largely focuses on the context of large companies or corporates, intrapreneurship can take place at any type or size of entity. This means intrapreneurship is just as relevant for non-profit organisations, government entities or small-and-medium sized enterprises.

For example, 60 decibels is a social enterprise focused on impact measurement that developed from a project spearheaded by an intrapreneurial team within Acumen and later became a spinout.

Both the U.S Department of Justice (DOJ) and the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) encourage a culture of intrapreneurship. DOJ and GAO operate ‘Employee Suggestion’ programmes wherein ideas that promote efficiency are recognised by the organisations’ leadership. Further, GAO offers mentorship programmes that provide budding intrapreneurs the opportunity to explore ideas and receive critical feedback. The dialogue also provides an opportunity for employees to enhance their skills and knowledge base.

In addition, intrapreneurship activity at large companies or corporates may also focus on addressing social issues rather than being purely for-profit. For example, Myriam Sidibe led one of the biggest public health campaigns from within Unilever aimed at changing handwashing behaviours of one billion people. She has since published a book, Brands on a Mission, about the power of brands to solve global health challenges and has become one of the world’s leading voices in this area.

University intrapreneurship programmes

Looking across the UK and US, relatively few university schemes exist that are specifically oriented around intrapreneurship or branded as such. Among the ten programmes reviewed during this exploratory study, they roughly fall into four categories: extracurricular schemes, structural change in existing programmes, minor/concentration at the undergraduate level and taught masters (see Figure 2).

From these, the following discussion focuses on three schemes—the ABaCuSS Scheme, the Marymount Intrapreneurship Initiative and York’s MSc Engineering Management programme.

Figure 2. University intrapreneurship programmes

- ABaCuSS (The Accelerator for Business Challenges and Social Science)

Funded by Aspect, ABaCuSS is designed to inspire innovation through collaboration between business and PhD researchers in social science. ABaCuSS is a collaboration among the Universities of Glasgow, Manchester and Sheffield and is spearheading intrapreneurship as a model for accelerating the impact of social science research.

In an Aspect webinar from September 2020, ABaCuSS programme staff discuss how they designed and operationalised the pilot extra-curricular intrapreneurship scheme (see Figure 3 for an infographic from the webinar). In developing its pilot, ABaCuss targeted second year PhD students for tailored eight-week long intrapreneurship placements with firms. Second-year PhD students were chosen because, on the one hand, they have more expertise and confidence than first-year PhD, master’s or undergraduate students. At the same time, they are less busy with their thesis preparation than third-year (and beyond) PhD students. As a result, second-year PhDs are at a point in their academic journeys where they have credible expertise to offer and can present their expertise confidently to businesses, while also having the capacity to explore alternative pathways to generating impact.

During the July 2021 Q&A session led by the Entrepreneurship CoP, ABaCuSS programme staff also presented an update since implementing the pilot. One of the main questions raised during the session is understanding how the scheme contrasts with student consultancy projects. The main takeaway is that the ABaCuSS team works closely with the business partners to design placements that are tailored according to the expertise of the participating students. This contrasts with consultancy projects wherein it is more common for firms to pitch a particular problem that they aim to address, and student teams would then select into projects to work on.

Figure 3. Operationalising Intrapreneurship Infographic (Source: ABaCuSS webinar, September, 2021)

- Marymount Intrapreneurship Initiative (MI2)

Located in the Greater Washington, D.C., region in the US, Marymount University launched MI2 in 2019. Bolstered by regional economics research and a group of intrapreneurial leaders in the area, Marymount’s School of Business and Technology set a strategic policy to be intrapreneurship-centred.

MI2 argues that the most economically important entrepreneurial behaviour is not starting a new business, but rather it is the process for solving problems and creating new opportunities in existing organisations—that is, intrapreneurship. Marymount further contends that (relative to start-up entrepreneurship) intrapreneurship is particularly vital to their regional economy. Moreover, Marymount highlights that intrapreneurship skills and experience provides some of the best preparation for subsequent start-up entrepreneurship.

MI2 aims to support events and research that raise awareness of intrapreneurship’s criticality to the region’s economy and beyond. To achieve this, the initiative predominantly involves three strands of activities. First, the scheme seeks to broadly integrate intrapreneurial training into the curriculum at the School of Business and Technology, positioning Marymount as the university that trains the Greater Washington region’s future intrapreneurs. Next, the initiative offers educational opportunities for existing organisation’s leadership to develop intrapreneurial approaches to growth and to understand how to attract and retain an intrapreneurial workforce. Finally, the initiative convenes thought leaders and organisations to share best practices of intrapreneurship and skills development.

The scheme has been especially helped by two additional factors: (i) it is led by a School Dean who is a prominent innovator in the Greater Washington region and (ii) it is supported by a group of prominent well-connected local intrapreneurs, who have generously donated their expertise and funds to launch and carry out the Initiative.

Box 4. Intrapreneurship vs. Entrepreneurship

Intrapreneurship and entrepreneurship are alike in many ways, as both require creativity, innovation, business acumen and goal-orientation (among other skills and capabilities) to bring new ideas to life. Yet they also differ in critical ways.

The following provides an overview of how they differ across four key dimensions. These differences, or sometimes trade-offs, may be used to help students understand which path may be more suitable to them based on their personality or risk preferences at given points in life, and/or whether intrapreneurship may be a more feasible route to actualise innovation in particular industries, etc.

Risk vs. Reward – Entrepreneurship is a high-risk, high-reward pursuit. Intrapreneurs have the relative safety of a pay check and therefore, their actions are lower-risk. However, at the same time, intrapreneurs typically will not expect to receive a share in the wider profits of a successful new product or business division.

Building culture vs. navigating one – Entrepreneurs build their own corporate culture, but intrapreneurs must adeptly navigate within an established one.

Autonomy and speed vs. structure and bureaucracy – Because entrepreneurs go into business for themselves, they tend to have more control over business decisions than intrapreneurs who operate within a more structured system of corporate checks and balances.

Resource Attainment – Some organisations provide manpower, funds and time for intrapreneurial activities, which may give intrapreneurs an advantage over entrepreneurs. This advantage is particularly pronounced in industries where traditional entrepreneurship is too expensive or where competition is too large. One of the great intrapreneurship examples is DreamWorks Animation, which offers classes in script writing to its animators so they can develop and pitch their own scripts within the company.

- MSc Engineering Management at the University of York

The course was launched in 2010 in response to demand for a management course designed specifically for engineers. It aimed to engender amongst students an entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial mindset as well as enterprise awareness. To achieve this, the course integrated taught coursework alongside active or experiential learning to enable intrapreneurial skills to be developed through reflection, collaboration and action analysis.

A review of this programme published in 2014 found intrapreneurship training at the university level to be lacking, especially when juxtaposed with intrapreneurship being a highly valued skill in the workplace. The review saw the MSc course as filling an important gap in what had been lacking in university offerings. The findings also singled out the programme’s distinct clarity in purpose and goals from its initial curriculum design phase to be critical to the success of such interdisciplinary programmes.

Interviews carried out with 15 alumni made it apparent that former students considered intrapreneurial capacity to be vital in an increasingly competitive and globalising corporate environment. Alumni also noted that having a mix of business and technical skills is important in being able to drive innovation in industry and that the programme’s experiential learning with real life team projects helped them to cultivate the mindset, skills and confidence to become innovators in their respective fields.

“Being innovative is a big part of my job…

I have to find new ways for solving a challenge in a project…

there’s always a need for thinking outside the box.”

Takeaways

Main takeaways from the exploratory study on intrapreneurship can be summarised as follows:

- Intrapreneurship is not a popularly used or understood term. This may pose a challenge for university programmes in designing communication around the value of intrapreneurship and in branding intrapreneurship-specific programming.

- Intrapreneurial capability is valued by employers. Harnessing employee innovation is important for corporates and non-for-profit organisations, alike. Recruiter polling also demonstrates that intrapreneurial ability is a highly desired skill in job applicants. Moreover, graduates relay that being intrapreneurial is vital to building a successful career in a highly competitive, global economy.

- Through university intrapreneurial programming are relatively scarce, the ones that exist span a variety of different approaches. From short-term industry placements to positioning as an intrapreneurship-focused university to interdisciplinary taught master’s courses, there is a wide range of approaches to what might be considered university intrapreneurship programming. The programmes may provide useful reference points for universities considering whether and how to develop and operationalise their own intrapreneurship schemes.

Conclusion

A preliminary study into intrapreneurship has found that while the set of skills and capability the term describes is valued by employers, the specific term itself is less popularly used or understood. On the one hand, this begs the question of why is it so? Then, what is the most effective way to communicate and brand intrapreneurial programming to best engage social scientists?

In terms of what intrapreneurship schemes at universities look like, the exploratory study has shown that a wide variety of approaches exist. While some universities offer a minor or concentration in innovation and intrapreneurship at the undergraduate level, others may choose to brand their masters programmes around intrapreneurial skill development. One of the most striking examples is that of Marymount University in the US, which strategically positioned its School of Business and Technology as intrapreneurship focused. Amongst extra-curricular schemes, there are intrapreneurship-oriented workshop series and industry placements for PhD students as well as flagship university accelerators that promote themselves as opportunities in supporting and showcasing both entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship.

Another key outstanding question is, what does this mean for social science? Are the social sciences potentially more inclined towards intrapreneurial (rather than entrepreneurial) pursuits? Are different considerations required in designing and operationalising intrapreneurship-specific schemes targeted at students from social science disciplines?

—

Want to learn more? Read other outputs from the Entrepreneurship Workshop Series project here: https://aspect.ac.uk/about/aspect-funded-projects/entrepreneurship-workshop-series/