In the UK, it seems that there is no standard base for where entrepreneurship sits within universities. This is evidenced among Aspect member institutions. For some institutions, entrepreneurship support predominantly sits within university careers department, while for others there may be a strong entrepreneurship and innovation hub within the business school.

At the same time, it is also not uncommon for entrepreneurship to sit in multiple places within a university, in a disjointed manner. For instance, the careers team offers entrepreneurship support, the business school runs its own hub along with accelerators, while the sciences and engineering departments may carry out their own support for incubating startups and spinouts. While it is sensible to have different entrepreneurship support available to meet the needs of students at different stages and (perhaps) different disciplines, this disjointed reality also translates into a level of duplication of efforts without enabling programmes to build from one another with synergy and an integrated vision.

What do different institutional arrangements have to do with revenue generation? First, depending on the institutional arrangement, there may not be a demand for an entrepreneurship hub to develop its own revenue streams at all. Secondly, the type of arrangement plays a role in how the hubs think about the underlying question of “why are we doing this?” How each hub answers the WHY question in turn informs thinking on the types of revenue streams to consider and the unique value proposition.

The Aspect Entrepreneurship Community of Practice led a knowledge sharing Q&A session to discuss and exchange learnings in this area, which are most applicable for entrepreneurship hubs that are facing pressures to generate revenue and/or facing a funding gap or are considering growing the programme’s remit. In particular, we share the context and experience of Aspect members, LSE and Bristol.

Institutional context

LSE presents a relatively unique case wherein the entrepreneurship support started within the university’s careers services and later spun out to become a standalone hub that serves as a school-wide base for entrepreneurship. Since becoming standalone, the hub started to receive additional revenue through direct donor funding, which has enabled the hub to not be completely financially reliant on the central institutional budget. However, the pace of programmatic growth and demands for services and support is increasingly outpacing the flow of donor funding. As a result, the hub is seeking to bring in new streams of revenue.

Bristol is in the process of creating an integrated entrepreneurship support strategy, led by the Research and Enterprise team. In its existing format, entrepreneurship support is offered by various parts of the university with little to no communication with one another. This has not only resulted in inefficiency but has also hampered the university’s ability to support students. In this siloed environment, the nature of support that students are able to access will be dependent on which part of the university they engaged with, rather than receiving an understanding of the holistic set of offerings across the institution in line with their needs and goals.

Impact of Covid-19 from a funding perspective

Though it is commonly understood that Covid-19 has exerted budgetary pressure on institutions, session participants also indicated an upside, which is that Covid-19 has boosted the status of entrepreneurship. Bristol shared that there is a growing view that entrepreneurship is the way forward for the economy and universities have a crucial role to play. Further, members anticipate an increased pace of government funding support for entrepreneurship.

LSE also relayed the experience of university messaging spotlighting student and alumni entrepreneurship initiatives in addressing social and economic impacts of Covid-19. However, this rise in stature from a communications and public relations perspective has not corresponded with increased allocation of funding from the institutional budget. Moreover, there is indication of a slowing pace in donor funding, which may or may not be directly related to Covid-19.

Revenue generation experience and plans LSE’s entrepreneurship hub is a strong proponent of actualising what they teach their students in terms of being agile and developing products through iteration and experimentation. We can see this evidenced in the innovative array of revenue generation initiatives that the hub planned to pilot or expand in the Michaelmas term 2020, outlined in Table 1.

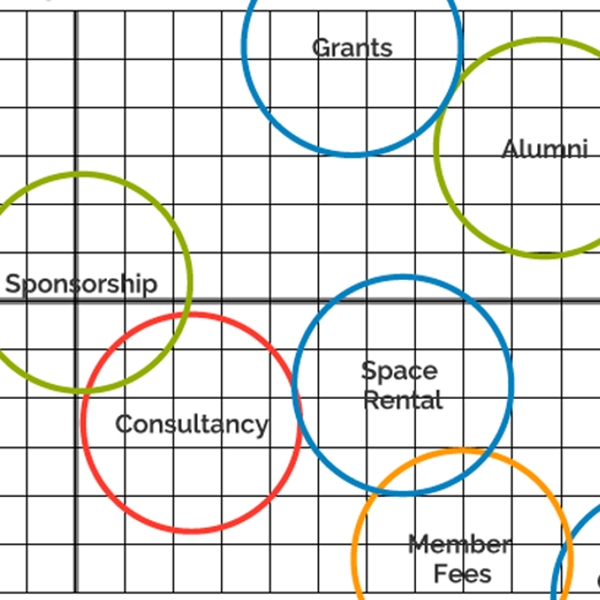

Figure 1 shows Bristol’s funding model, which is arranged along axes of scale and time horizon. In comparing two plans, we observe that many of the LSE initiatives explicitly or (appear to) implicitly target alumni (both as paying customers and as the end-user being supported). In other words, Bristol’s funding model is arguably more diversified.

That being said, Bristol’s funding model covers a wider remit of research and enterprise, which includes research commercialisation. Bristol relayed that intellectual property (IP) equity has provided substantial one-time revenues when there is an outsized exit, but given that the performance of these business are highly varied and unpredictable, it cannot be modelled as a reliable source of revenue. This type of research commercialisation is outside of the remit of LSE’s entrepreneurship hub and may not be as applicable for a social sciences-focused institution.

Another difference that we observe is that LSE’s revenue generation approaches are explicitly virtual, can include a substantial virtual component or can be adapted to a fully virtual format, whereas Bristol’s funding model includes physical space rental and membership fees for office space. However, this difference could be a result of different factors, from different student needs to different capacity or strategy for support.

Communicating value proposition to senior leadership

Both LSE and Bristol (along with a few other Aspect members) shared the challenges of effectively communicating their value proposition to senior leadership, though members share a common view that Covid-19 has boosted the stature of entrepreneurship. That being said, the particular relationship with senior leadership differs for the entrepreneurship hubs at LSE and Bristol. Again, this relates both to institutional arrangement and capacity to generate independent funding.

LSE’s entrepreneurship hub desires senior leadership to allocate more funding from the central budget to the entrepreneurship hub, but at the same time it has sufficient independent fundraising capacity to not be reliant on central funding. Perhaps, relatedly, the hub also holds substantial operational independence.

In contrast, Bristol’s Research and Enterprise team is more reliant on the institution for funding and operational remit: constantly having to justify its entrepreneurship support services to senior leadership. One of the challenges identified in communicating their value proposition lies in the limited ability to track the progress of student entrepreneurs post-graduation and, relatedly, difficulty in measuring and attributing outcomes or achievements of student entrepreneurs to the support of university entrepreneurship services.

Recommendations

This Q&A session offered a chance for Aspect members to share and offer learnings on innovating revenue generation. The following includes a few recommendations, with varying degrees of applicability depending on the particular institutional context and motivation:

- Ask WHY: First and foremost, it is important to understand the vision, motivation and logical framework behind (a) what is the aim of developing/expanding entrepreneurship services at the university and (b) how will innovating revenue generation support that aim. If it is a case where the entrepreneurship sees a clear demand from students that the senior leadership does not, then it is also important to understand why. Further, in determining how innovating revenue generation will support the aim of expanding entrepreneurship support for students, at the same time, it is also important to consider any potential inadvertent effects of particular funding models.

- Band together: Universities face a similar macro environment that brings both challenges and opportunities. Covid-19 has borne a particularly significant effect on the stature of entrepreneurship and, at the same time, it has put general budgetary pressure on institutions. Therefore, it is in the interests of institutions to share resources, identify opportunities for joint revenue generation initiatives and develop a common platform to communicate and advocate for the importance of entrepreneurship for the UK and the critical role of universities.

- Engage alumni: Engaging alumni is invaluable. They are a resource for current students and provide potential funding streams. Moreover, developing alumni entrepreneur case studies helps in communicating the value proposition to senior leadership. To reach alumni entrepreneurs, utilise current student entrepreneurs as ambassadors. Founders speak the language of founders and are likely to be much more effective at reaching alumni than university alumni relations teams.

- Get feedback now: Given that it may be more challenging to reach students post-graduation, obtain regular feedback from students on how the university entrepreneurship services have added value to their journey. Closer-to-real-time feedback not only can be used to communicate the value proposition to senior leadership, but can also shorten the feedback loop to enable university entrepreneurship hubs to experiment, learn and adapt programming more nimbly in response to student needs.

Conclusion

In the UK, we observe that there is no standard base for where entrepreneurship sits within universities. This is evidenced among Aspect member institutions. Depending on institutional context, entrepreneurship hubs may be seeking to develop an independent revenue stream or plug a funding gap. The Aspect Entrepreneurship Community of Practice led a knowledge sharing Q&A session to discuss and exchange learnings in innovating revenue generation in the midst of the Covid-19 macro environment.

Through understanding the revenue generation experience and plans of Aspect members LSE and Bristol, we have seen differing constraints and funding approaches. From this we have aimed to distil a few recommendations that may be useful for institutions seeking to develop a new funding model. That being said, it is broadly applicable for universities to seize the challenge and opportunity presented by the Covid-19 macro environment to develop a common platform to communicate and advocate for the importance of entrepreneurship for the UK and the critical role of universities in catalysing the entrepreneurship ecosystem.

Wen Chen, LSE School of Public Policy ’18