Slides

Panel members

- Rachel Gibson – Professor of Political Science, University of Manchester

- Dr Ariadna Tsenina – Research Associate, Democracy@Risk Project, University of Manchester

- Professor Martin Innes – Director, Crime and Security Research Institute & the Universities’ Police Science Institute and a Professor in Social Sciences

- Dr Vladimir Barash – Science Director, Graphika

Session summary

As part of Aspect’s 2020 Annual Event series, exploring how social sciences innovation can contribute to building wellbeing and prosperity, Rachel Gibson (Professor of Politics at the University of Manchester) and Ariadna Tsenina (Research Associate on the Digital Information Literacy Programme for Schools project) were joined by Martin Innes (Director of the Crime and Security Research Institute at Cardiff University) and Vladimir Barash (Science Director at Graphika) for a panel discussion exploring the role the social sciences have to play in combatting the spread of misinformation online.

The topic is certainly pressing. With the advent of social media, society has found itself awash in a sea of misinformation, ranging from fake news and conspiracy theories, peddled by naïve but well-meaning citizens, to deliberate disinformation campaigns orchestrated by hostile state actors, with the intention of subverting the political integrity of rival nations and gaining advantages for themselves.

Responses to these threats by governments or the owners of social media platforms, however, have often been piecemeal, uncoordinated and ineffectual. In the session, the panellists discussed what the social sciences can tell us about the dynamics of online misinformation and how efforts to curb this threat can be improved.

Ariadna Tsenina kicked off the session by presenting findings from the final report of the recently completed Democracy@Risk project, written by herself, Rachel Gibson and Emma Barrett (Professor of Psychology, Security, and Trust at the University of Manchester). Her presentation contained a number of important learnings on how online misinformation can be more effectively conceptualised and combatted using insights from the social sciences.

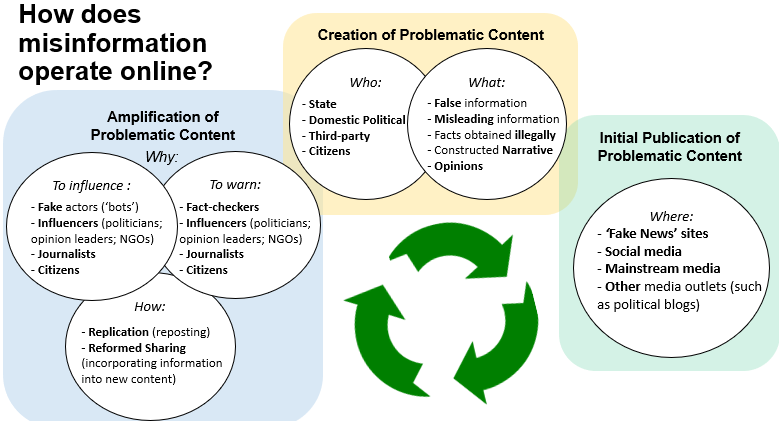

Among the most important of these insights is that a wealth of social sciences research points to the fact that the publication and dissemination of misinformation online is best understood as taking place within a complex eco-system, featuring a wide range of actors, types of content and pathways for the spread of problematic content.

Another crucial finding is that fact-checking, by far the most common response of authorities to online misinformation, falls far short of providing a one size fits all solution to this problem. This is because while fact-checking has some potential to inform voter choice and neutralise misinformation, it often is of limited effectiveness and can come ‘too little too late’, as citizens exposed to the original misinformation fail to see corrected claims or because political affiliation leads to the citizen rejecting the authority of the fact checking exercise.

The Democracy@Risk team thus found that corrective approaches, such as fact-checking, must be supplemented with more preventative strategies in order to be fully effective. Potential forms that such preventative strategies could take include:

- Creating common practical standards and pre-publication support for influencers and officeholders on social media to support them in identifying and avoiding spreading online misinformation;

- Redesigning social media platforms to encourage mindful consumption and creation of information online through behavioural ‘nudges’; and

- Empowering citizens to identify, avoid and tackle online misinformation effectively.

This latter approach has been taken up by the new Aspect-funded project, DILPS (Digital Information Literacy Programme for Schools), which explores how the findings from research on political misinformation and digital information literacy (DIL) can be transferred into the secondary education curricula by social enterprises specialising in civics education in order to create effective and accessible resources on DIL for use by teachers in schools.

Overall, Ariadna stressed that the understanding of human behaviour and social relationships offered by the social sciences is crucial for combatting the harmful effects of online misinformation. Initiatives such as DILPS offer promising examples of what this role looks like in practice.

Martin Innes followed this with a presentation drawing on insights from his own work leading a major research programme exploring the dynamics of misinformation across 12 European countries. He offered a sobering assessment of the scale and seriousness of the problem, explaining that disinformation campaigns across Europe are employing increasingly sophisticated methods to hijack and manipulate online sentiment around a variety of high profile events such as assassinations, terrorist attacks and political scandals with the long-term aim of undermining social cohesion and trust in political institutions.

The actors behind such campaigns are notably becoming much more adapt in disseminating problematic content, making concerted efforts to target influencers, politicians and celebrities who can amplify misinformation in order to maximise its harmful effects. Martin provided a number of case studies drawing from his research to illustrate these trends, including a fascinating deep dive into the developing tactics of the Russian-linked Internet Research Agency, which infamously was found to have attempted to influence the course of the 2016 US Presidential elections through social media manipulation. He concluded by looking forward to the future, predicting that the scale and intensity of misinformation that will be seen in this year’s upcoming presidential elections is likely to be unparalleled.

Vladimir Barash, Science Director at Graphika, rounded off the session with a fascinating presentation showing how the company uses sophisticated social science methodologies to map out and analyse the publication and dissemination of false and inaccurate content online. Their proprietary software combines machine learning with social network analysis to provide large-scale, real time mapping of flows of information in online communities. Using this technology, they’ve not only worked alongside governments, well-known media outlets such as Reuters, and similar clients to identify and analyse disinformation campaigns, but also to provide services in digital marketing and strategic communications.

Vladimir used the example of international discourse around the Hong Kong democracy protests as a case study, showing how Graphika’s mapping technology can be used to identify flows of misinformation in online communities, in this case by Chinese Government aligned disinformation teams using ‘spamouflage’ to cloak their actions and promote anti-protester talking points. Vladimir concluded by stressing that, alongside the more well-known risks to political processes and social cohesion that misinformation poses, they can also pose serious threats to corporations via fake boycott movements and targeted harassment campaigns that can harm companies’ public image.

Graphika’s role in identifying and tracking online misinformation is therefore crucial, and its work will likely only grow in importance in the coming years as online communication occupies an ever more central place in our social lives, our politics and our business dealings. Having its origins as a commercial spin-out started by an academic, in occupying this role Graphika stands out as an example of exactly the kind of excellence in social science commercialisation that Aspect stands for and champions.