What gets measured: how social science innovators are venturing into the market

By Horatio Mortimer

Corporate investment is moving away from tangible assets like machines and buildings and towards intangibles — things that are hard to measure, like research & development, business processes, and human capital. Horatio Mortimer writes that the pressing need for measurements that are hard to make and results that are hard to manipulate presents opportunities for social scientists, who are stepping forward to provide solutions.

“What gets measured gets managed” is a well-known business mantra probably wrongly attributed to Peter Drucker. The exhortation is to measure performance wherever you can, because people will be judged on the things that are measured, and so neglect the things that are not. This applies at all levels where decision makers rely on data, from within an organisation to government policy.

What about those things that cannot easily be measured? Are they therefore doomed to be neglected?

As more and more measurements are taken, and the amount of data collected rises exponentially, measuring and optimising performance has become feasible over more and more domains. But does this accelerating efficiency create more and more distinct areas of neglect, and more and more powerful negative externalities in domains where measurement is absent or defective?

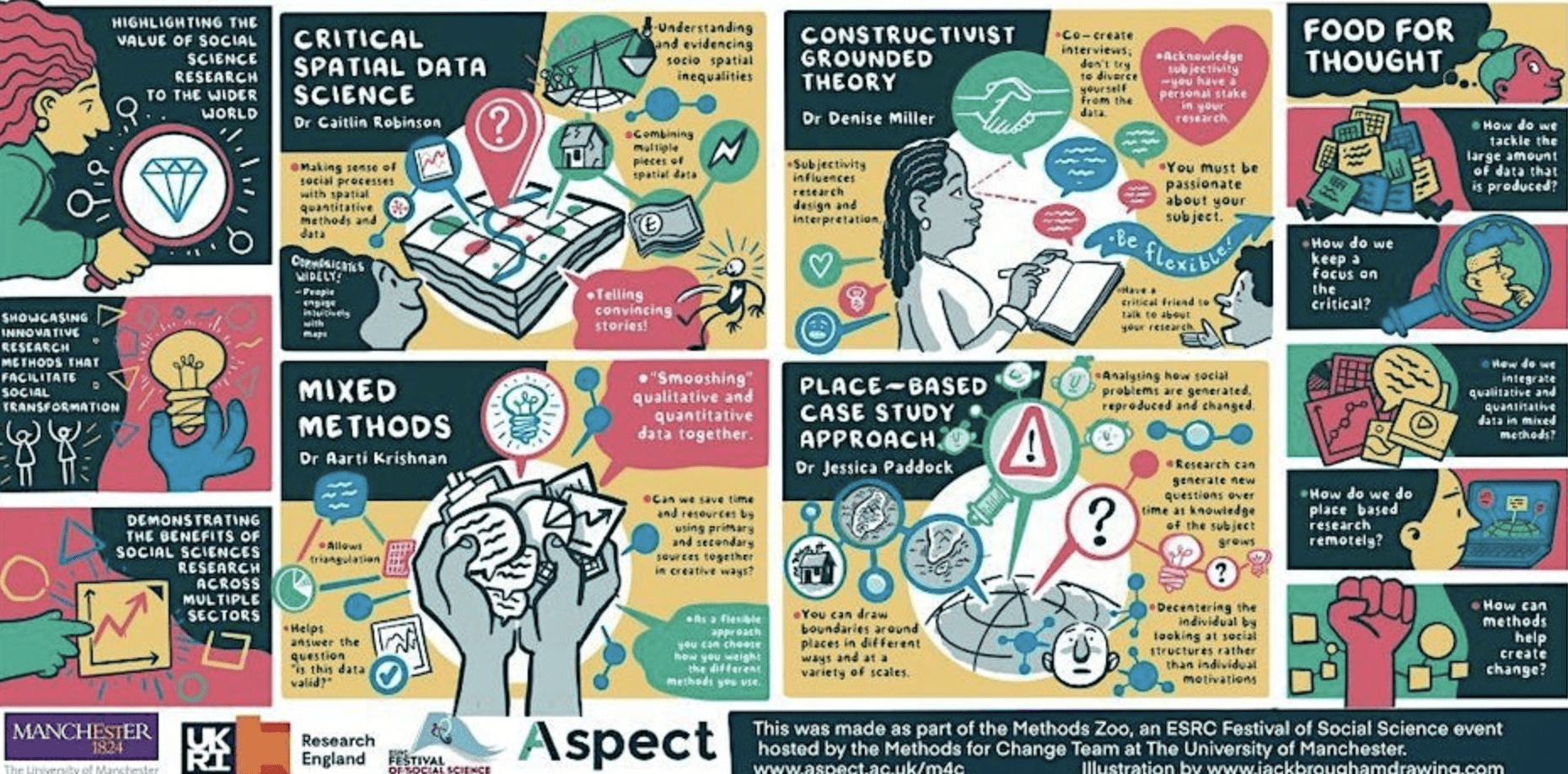

Social science

A good many social scientists are concerned with measuring things that are complex and very difficult to quantify. Natural sciences are complicated enough, but social sciences often include the extra complication that the measurements themselves can change social behaviour and alter the results. Thus LSE professor Charles Goodhart coined the maxim now known as Goodhart’s law that any measure used as a target loses its value as a measure. In other words, those measures that get managed, get manipulated.

To make matters worse, some of the world’s most transformative companies have been built by engineers who did not understand the social impacts of their products, resulting in colossal unintended consequences. Things that were not measured were not managed.

Traditionally, social science has sought to achieve impact through influencing government policy. Perhaps partly for that reason, some social scientists have avoided venturing into the private sector – being keen to avoid having any personal vested interest in their policy area.

It seems though that this pressing need, for measurements that are hard to make and results that are hard to manipulate, presents opportunities for social scientists, who are stepping forward to provide solutions.

Transition Pathway Initiative

My work is to support academics who want to increase the impact of their research through enterprise and who feel that their valuable ideas will not be put into practice unless they do it themselves. Many of the projects we help with are seeking to commercialise (not always for profit) clever ways of measuring things that are hard to measure, and ways to stop those measurements from succumbing to Goodhart’s Law and becoming distorted.

For example, the Transition Pathway Initiative (TPI) measures listed companies’ preparedness for a low carbon economy. TPI was founded by a consortium of investors led by the Church of England Pensions Board and the Environment Agency Pension Fund. LSE became TPI’s academic partner and FTSE Russell TPI’s data partner. It has a carefully balanced governance structure to safeguard the objectivity of its methodology. TPI is now supported by 130 investors with over $50 trillion of assets under management.

Governments, companies and investors are all moving towards measuring those external costs that have been neglected by the market. People investing for their pensions do not want those investments to cause damage to the world they will inhabit when they draw down those pensions. This partly explains the dramatic rise in environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) investing that aims to mitigate long term risks for investors.

Methodologies (such as TPI’s) for measuring environmental and social impacts are being increasingly adopted and incorporated properly into international accounts. These in turn are beginning to dissuade companies from creating and adopting technologies that exploit things they did not have to pay for that create external costs to society and the environment; and it is prompting them to look for tools to measure their external impacts. Many governments are also beginning to look beyond GDP as the sole measure of success.

Other social science innovations are finding ways to make organisations and institutions more inclusive by giving voice to previously marginalised stakeholders. These too can deliver more resilient growth.

Addressing the ‘intangible’ problem

Meanwhile, there has also been a fundamental shift in the economy as corporate investment moves away from tangible assets like machines and buildings and towards intangibles. ‘Intangibles’ is something of a catchall category for things that companies spend money on that are hard to measure, like R&D, design, and marketing, but also new business processes, including methods for improving outcomes that are hard to quantify, and human and social capital (e.g., training and teambuilding). Furthermore, the move away from narrow shareholder-value investing to wider stakeholder-value models such as ESG has also added to the intangible investment categories with measurement challenges.

Intangibles are often absent from company accounts, and when they do show up, they are treated as sunk costs. They are sunk because they can’t be traded, and they can’t be traded because they do not carry clearly defined property rights. Why do they not carry adequate property rights? Is it sometimes because they are difficult to measure?

Social science solutions themselves are often at the most vaporous end of intangible. They are rarely inventions that can be patented, and copyright IP is easily circumvented and difficult to protect. As such they are not often well-suited to development with investment finance within established companies, because they do not qualify as collateral against which to raise debt. Also, they may be disruptive to the company’s incumbent business model, or the techniques may easily be captured by their competitors who have not had to invest in developing them.

There are some reasons, though, why these commercial solutions may be well-suited to start-ups. They do not require huge amounts of start-up capital. If they are scalable and disruptive, then they are potentially attractive to venture capital funds who invest in exchange for equity. In the past, the problem has often been that social science techniques are quite labour intensive and often sold as consultancy services rather than stand-alone products. However, automation and artificial intelligence are changing this pattern, making some of these techniques easier to turn into software products, and also making consultancy easier to scale up.

Commercial innovations to generate public goods

One of the most far-reaching technological developments of recent years has been the change from a cascading top-down media system of information distribution to the chaos of social networks. This has brought opportunities but also threats. As mentioned above, the tsunami of new data enables a myriad of new ways to make use of it. On the other hand though, it also generates a gargantuan rat race as everybody competes to rise to the top – of search results, or any number of league tables or status metrics (e.g. ‘likes’) both for organisations and for individuals. And all of these are vulnerable to Goodhart’s law and its distortions, with whole industries growing up to help people game the results, wasting resources and debasing the information.

On top of that we have bad actors including rogue states manipulating our human frailties in order to spread disinformation and division. Sometimes, their principal objective is to undermine the social trust that governments need to effectively regulate the economy and provide public goods. Even when that is not the objective, it can still be the effect.

These are fundamentally intractable problems that require good government to resolve, while at the same time making good government more difficult to achieve. Social scientists have always been in the business of understanding and explaining such problems and proposing policies to address them. Now more and more of them are also exploring market solutions that can provide public benefits and enable good government to get back on its feet.

Social scientists are developing solutions to combat disinformation. Ways to help people find good information and understand and trust its provenance (e.g., the TPI metrics) are only one example.

These problems are created by failures to measure and manage vitally important consequences of technologies that have fundamentally changed society. Finding solutions to them are the most pressing challenges facing liberal democracies. They are also an opportunity for social scientists to scale up the real positive impact of their research.

Horatio Mortimer is Business Innovation Manager at LSE Research and Innovation. Horatio first came to work at LSE Enterprise 20 years ago, after having worked at the United Nations in New York. More recently, he has worked in public affairs consultancy and venture capital, specialising in renewable energy technology. Horatio has a Post Graduate Diploma in Finance and an MSc in Financial Economics from Birkbeck.

This blog was originally published on the LSE Business Review Blog

Image by Valentin Antonucci @Pexels